God Of Love – KamaDev

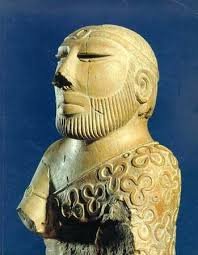

God Of Love – Kama Dev In the ancient Indian scripture Rigveda, we first meet Kamadeva (kamadev). His name joins ‘kama,’ meaning desire, and ‘deva,’ God, and thus he’s known as the ‘God of Desire’. An interesting way to picture him? Imagine a person flying on a parrot, holding a bow made from a sugarcane stalk. Now, think of the bow string – it’s a line of buzzing bees! As for his arrows, they’re not the usual ones. They’re flower-tipped, symbolizing desire. That’s Kamadeva’s unique way to spread love – those arrows can make anyone fall in love! Tale of Lord Shiva and kamadev Kamadeva was cursed by Shiva and was finally brought back to life only after Shiva and Parvati were happily married! There could be two reasons for this. For starters, Kamadeva was considered a part of the Vaishanava tradition, thought to be Vishnu and Lakshmi‘s son. Later on, Krishna took over as the ideal lover. Krishna, one of our most widely beloved gods, is perceived as the timeless lover alongside Radha and the gopis. In Mathura, there’s even a trace of a festival dedicated to the local god of love – Madana, that was absorbed by Krishna’s followers. There is celebration in the city that used to be the Madana Leela is now honored as Krishna’s Raas Leela! Kamadeva, a character dating back to the Rigveda, has a name that simply means ‘God of Desire.’ His description is vivid, involving him riding a parrot and holding a bow crafted from a stalk of sugar-cane. This bow is strung with a line of bees that hum. His arrows? They’re not your common ones. They’re flower-tipped, representing desire itself! Supposedly, their influence can make anyone fall in love! The Indian Kamadeva, the Greek God Eros, and the Roman Cupid share clear similarities in storytelling. The most outstanding story is when Kamadeva disturbed Lord Shiva‘s meditation to help Parvati, a king’s daughter, get his attention. Shiva, upset by the intrusion, lashed out at Kama with a curse. The love God returned to life once Shiva and Parvati tied the knot. It appears Kamadeva never truly bounced back as there aren’t many stories about him afterward.

BEST HISTORICAL WALK IN DELHI

HISTORICAL WALK IN DELHI Delhi, now India’s capital and political hotspot, wasn’t always so. Its roots trace back to the Pandava Empire’s capital, Indraprastha, from the Mahabharata. But without much archaeological evidence, its precise whereabouts and reach remain unclear. Locals believe that Purana Qila’s Kal Bhairav temple was established by Pandava Bhima. Here, ancient, painted grey earthenware vessels present even more history. At least 2,000 years old, they indicate powerful economic day-to-day activities during Rig Veda’s final formation. Changes shifted Delhi’s rule from the Maurya and Gupta empire over various centuries. Around the 11th century, the Tomar family, Delhi’s early rulers, built the fortified city of Lal Kot—Delhi’s precursor. The influence of the Chauhan dynasty, led by Prithviraj Chauhan, soon spread throughout the region until his defeat by Muhammad Ghori at the Second Battle of Tarain in 1192. ERA OF SULTANATE IN DELHI Post-defeat, Muhammad Ghori established the Ghuri dynasty and the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 under Qutb-ud-din Aibak, a former slave and general. This began Muslim rule in Delhi. Over time, Hindavi, Delhi’s local language, became the Deccani barracks language, later known as Urdu. The Delhi Sultanate’s reign extended across various dynasties—the Mamluks, Khiljis, Tughlaqs, Saids, and, finally, the Lodi dynasty. This period marked the birth of “Indo-Islamic” architecture with the iconic Qutub Minar and Siri Fort. The Tughlaqs also built multiple cities. Among them, Tughlaqabad, Jahapanah, and Firozabad. Lodi Gardens, home to 15th-century Lodi Tombs, still buzzes with cultural activities. In 1398, Central Asian conqueror Timur wreaked havoc on Delhi in what is infamously called the “Sack of Delhi.” VENTURE IN DELHI Skipping forward, the 16th-century Mughals’ arrival marked Delhi’s revival. They ruled from Agra initially then shifted their capital to Delhi, establishing Shahjahanabad. After Persian ruler Nadir Shah brutally sacked Delhi and looted the Koh-i-Noor diamond, the British moved their capital from Kolkata to Delhi. The plan was to build wide streets and colonial-style architecture, such as Rashtrapati Bhawan. This new city, designed by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, is today’s “Lutyens’s Delhi.” Post-Partition, refugees flooded into Delhi, causing a dramatic demographic shift. This called for new public art that espoused democratic and republican ideas and replaced imperial art , manifested in Parliament’s 21st-century building featuring iconic animal symbols- features Gaja (elephant), Ashwa (horse), Sahdra (lion), Makar (dolphin), Hamsa (swan) and Garuda (eagle).

Kissa Shiva Ka In Mahabharata

Kissa Shiva ka In the classic Hindu legend, the Mahabharata, there’s a tale told by Bhisma to Arjuna. It’s about a clash between Shiva and Daksha. Daksha snubs Shiva by not inviting him to share in a special ritual. In response, Shiva wrecks Daksha’s ceremony. This incident is said to have taken place in a location known as Ganga-dvara. Many people think this place is what we now call Haridwar. Our epic does not talk about Sati. The common tales say she’s Daksha’s kid and also Shiva’s spouse. They say she ended her life on her dad’s fire altar. Why? Because he did not invite her husband to his event. Not a single mention of Sati’s lifeless body held by Shiva. Or about pieces of it scattering across India. Those places later became known as Shakti-pitha, places with temples to a Goddess. The tales of Sati and Shiva only started to come out between 500 AD and 1000 AD. The Mahabharata is much older, dating back to 100 BC. The story of Mahabharata introduces Shiva’s spouse as Parvati. Shiva’s partner, however, is named Uma in the older Kena Upanishad, where Shiva represents the ultimate life force, Brahman. Here, no reference to Sati exists. This means that the concept of Shiva with two brides—one the offspring of Daksha, the other the child of Himavan—materialized later in time. Notably, despite Shiva’s austere lifestyle, his initial partner Sati was a Brahmin’s child, and his subsequent spouse Parvati was a Kshatriya’s daughter. People often link Shiva’s beginnings to the Veda, around 1000 BC. The god Rudra, a bit of an enigma, embodies this link. He’s a wild dweller, a cattle guardian, and has ties to both illness and healing. He wields a bow, uses an arrow to halt the first father’s pursuit of his daughter. Daksha’s link to Rudra appears later on. Then come tales of his marriage and offspring. All this shows how Shiva’s tales have evolved with time, geography, different cultural needs, and obstacles. The time after 1000 BC saw the flourish of Vedic culture, set amid Ganga and Yamuna’s doab. It was here that people built upon Vedic practices, holding tightly to their nomadic past with no temples or persistent shrines. Epic tales of Devas battling Asuras began here. It was said that Devas and Asuras, despite being half-brothers and children of Prajapati, the first being who later was known as Brahma, fought fiercely. The root of their conflict?- was Resources. In about 500 BC, our material-focused world met new ideas from monks originating further along the Ganga River. Regions like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Bihar birthed these thoughts. Buddhism stands out among these monk-led orders. Buddha, the originator, was once a recluse who morphed into a family man, according to Buddhist legends. The Mahabharata introduces us to Shiva, a recluse who also becomes a family man. The Ramayana adds to Shiva’s story, explaining how Shiva helped the Ganga river descend from heaven to bring revival to deceased kin. By the year 500 AD, tales of Shiva had hit the mainstream. He dared to challenge both Buddhism and the established Vedic practices. Shiva was portrayed as a hermit-turned-householder, representing a rejection of monastic life. He also disrupted Vedic yagna, a clear refusal of Brahmanical ceremonies. His depictions cropped up on India’s west and east coasts, promoted by Kalchuri, Chalukya, and Pallava rulers overseeing trade and ports. Temples presented him overpowering Ravana, the Ramayana’s antagonist, when he tried to seize Shiva’s Mountain home, Kailash. Around the year 1000 AD, Brahmins and kings reached further into tribal lands. Here, they tried to please the Goddess with Tantra rituals. These involved blood, alcohol, and sex. Images of Shiva prostrating before Kali were common. He would seek her assistance in wars, provide offspring for her, and partake in meals from her kitchen. Once the untamed Goddess got attention from Shiva, who was no longer an ascetic, she turned domesticated. By the year 1500, Islam firmly roots itself in India. The act of eating meat becomes associated with outsiders, leading to an intrigue of contamination. Popular trends now lean towards purification ceremonies. Shiva’s previous tie with tribal people and the ritually unclean cremation site is subtly reduced. An increasing number of deities known for consuming blood begin to prefer a vegetarian diet – a transformation first initiated by Jains, and later adopted by Brahmin wanderers such as Shankaracharya. Muslim leaders perceive the divine in a formless manner, hence the Shiva-linga symbol becomes more abstract, signifying the soul, while its phallic nature becomes less notable. The devotion to the blood-calling Goddess prevalent in Bengal, Assam, and Odisha presents an alternative to the more orthodox adoration movement focused on Ram and Krishna, where the sensual shifts into a spiritual, conceptual, and asexual sphere. In our modern era, ‘sanatana dharma’—or a timeless, steadfast faith—is becoming a popular tagline for Hinduism. This term, native to Vedic, Buddhist and Jain texts, essentially relates to theories of reincarnation, where the world and life have no origin or termination. Everything flows cyclically, diverging from the Christian and Islamic belief in a single life. ‘Sanatana dharma’ does not imply that Hinduism, Buddhism, or Jainism are unchanging faiths. There exist both consistencies and inconsistencies, changes springing from various historical and geographical circumstances, which birth the variety and dynamism of traditions. No need exists for their unification. By the year 1500, India is firmly under Islam’s influence. Consuming meat becomes associated with foreigners, implying contamination. Rituals for cleaning grow in popularity. Shiva’s prior association with tribal people and the symbolically unclean cremation site gets less attention. More blood-thirsty goddesses switch to plant-based diets, an idea first introduced by the Jains, but later adopted by wandering Brahmins like Shankaracharya. Under the new Muslim governance, the divine has no physical form. Shiva-linga begins to represent the soul abstractly, reducing its phallic connotation. In Bengal, Assam, and Odisha, the devotion to the goddess who thirsts for blood opposes the purist worship of Ram and Krishna. Here, all things sensual