Legends of Dwarka

Legends of Dwarka Krishna‘s worst fear came true. With sadness, he watched his cherished Dwarka transform into a city of excess and vanity. The Yadavas had gained immense wealth and sunk deep into debauchery, prompting Balarama to prohibit wine. Yet, during a festival at Prabhas Patan, they defied the ban and, filled with wine, began a killing spree in their drunken state. When Krishna witnessed the death of his son Pradyumna and grandson Aniruddha, he alongside Balarama, lost all motivation and retreated into the forest. यदा यदा हि धर्मस्य ग्लानिर्भवति भारत। अभ्युत्थानमधर्मस्य तदात्मानं सृजाम्यहम् ॥ Balarama left this world first, followed by Krishna, the victim of a hunter’s poisoned arrow mistaken for a deer. Krishna ascended to heaven and unified with the god’s radiance. Post his demise, Dwarka also vanished when a colossal tidal wave swept away its grandeur. Prior to his ascension, Krishna had instructed his charioteer Daruka to bring Arjuna, his friend. On Krishna’s command, Arjuna escorted Dwarka’s women and children to Hastinapur. In the Mahabharata, Arjuna describes Dwarka’s final moments as the ocean god, Samudra, claimed the land lent to Krishna. In his words, “I watched the beautiful buildings submerge one after the other. Within moments everything was swallowed. The ocean calmed, leaving no trace of the city. Dwarka is now just a memory.” Krishna‘s demise marked the end of the third Hindu era, Dvapar Yuga, and the beginning of Kali Yuga. Krishna’s great-grandson, Vajranabha, restored the lost kingdom. He travelled back to Dwarka’s coast and built a temple in Krishna’s memory, which became the original Dwarkadhish Temple. Considered one of the most sacred Vaishnava tirthas, Dwarka pays homage to Vishnu’s eighth avatar, Krishna. Known as Dwarkadhish and Dwarkanath, Krishna is the lord of the city. Affectionately known as Ranchhodji, the battle-leaver, and Trivikrama, the grand ruler of the three worlds.

Krishna And Mahabharata

Krishna And Mahabharata In the grand saga of the Mahabharata, Krishna shines as a king, fighter, leader, and thinker. He’s a layered character who has intrigued admirers and scholars for ages. His tale intertwines with that of two cousin groups, the Kauravas and the Pandavas, and their struggle for power. Ruling various kingdoms, they compete fiercely, leading to a deceit-filled game where the Pandavas are robbed of all they hold dear, including their honor. In their darkest hour, Krishna steps in to save the day, protecting them from Dusshasan’s cruelties. The tension escalates, war looms, and each side rallies allies. Both Duryodhan of the Kauravas and Arjuna of the Pandavas covet Krishna’s alliance. However, Krishna maintains neutrality, offering only his chariot services, not his physical participation. Interest piqued, Arjuna opts for Krishna, leaving Duryodhan with Krishna’s formidable army. Thusly, Krishna, the remarkable king, assumes the humble duty of a charioteer. As historian Irawati Karve notes, Krishna’s unbiased guidance was the crucial key to the Pandavas’ plan. यदा यदा हि धर्मस्य ग्लानिर्भवति भारत। अभ्युत्थानमधर्मस्य तदात्मानं सृजाम्यहम् ॥ This strategic prowess amplifies Krishna’s heroism in the grand narrative. The battle begins and Arjuna staggers morally, his affection for his relatives making him hesitant to fight. He gets disheartened, laying down his weapons. Krishna‘s counsel becomes Arjuna’s fortitude, encouraging him to persist. These powerful words are encapsulated in the Bhagavat Gita, a Hindu philosophical masterpiece that stresses duty and karma. The philosophy inspires many today, promoting a balanced lifestyle with measured actions, as Krishna advises. With the Pandavas victorious, Krishna returns to Dwarka, shadowed by a hefty curse. He witnesses the eradication of the Kauravas in battle, a tragedy that Gandhari, their mother, links to Krishna. Her curse binds him to a grim destiny: observe his kinsmen destroy themselves.

Lord Krishna’s City-Dwarka

Lord Krishna’s City-Dwarka Lord Krishna moved his family from Mathura to Gujarat, coastal India. They created a city next to the sea, named Dwaravati or Dwarka. This city prospered as long as Krishna stayed and it disappeared beneath the ocean when he died, suggesting its existence depended on him. Dwarka never forgot Lord Krishna. His dynamic spirit still touches this peaceful coastal city. He is honored every day at the grand Dwarkadhish Temple with lamps, flowers, incense, and chants. Folks sing hymns and perform ecstatic dances. They consider him Dwarkadhish, the superior lord of Dwarka. Dwarka appears often in the scriptures of the “Mahabharata“. Here, many stories of the Pandava brothers from Hastinapur take place. Arjun often visited Krishna and ended up marrying Krishna’s sister, Subhadra. Different scripts, such as Harivamsa, Bhagavat Purana, Skanda Purana, and Vishnu Purana mention the city too. People believe it’s a place where you can attain spiritual liberation from the cycle of life and death. Although the ancient stones of Dwaravati are now deeply beneath the Arabian Sea, Krishna’s caring spirit invites every pilgrimage from across the country. Krishna’s Life Krishna grew up near the Yamuna River in Mathura-Vrindavan, in what we now call Uttar Pradesh. But why did he set up his kingdom so far away in Gujarat’s Dwarka? This epic journey of the Yadava tribe is an intriguing story from the Mahabharata. The plot thickens when Krishna and his older brother Balarama overthrew their wicked uncle Kansa, the self-made king of Mathura. Kansa had taken the crown and sent his own father Ugrasen to prison. Afterwards, Ugrasen was reinstated as king but the real ruler of Mathura was Krishna. This change in power made Mathura an enemy of Jarasandha, the mighty king of Magadha. His two daughters had married Kansa, so Jarasandha despised Krishna. Additionally, Jarasandha dreamed of ruling an empire and had captured many local kings. But Krishna and his Yadava warriors stood in his way. Despite losing to Krishna eighteen times, Jarasandha wouldn’t admit defeat. Krishna knew he could win again but the constant battles had worn his people down. As if things weren’t tough enough, Jarasandha’s partner Kalyavahan, the Yavana king, planned to attack from the west while Jarasandha readied his troops for a nineteenth attack from the east. To protect his people, Krishna decided to escape the repetitive battles. He led his tribe across North India to distant Saurashtra. Krishna picked a place to settle that was guarded by the sea on one side and round hills on the other. Dwarka was so safe that Jarasandha never threatened them again there. Krishna even earned a new nickname in Dwarka, Ranchhodji. ‘Ran’ translates to battlefield and ‘chhor’ means to quit. So Ranchhodji describes a king who left the battlefield.

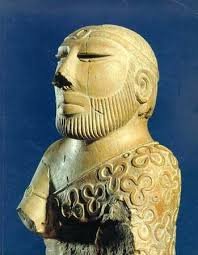

SEAL AND SHIVA OF INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION

SEAL AND SHIVA OF INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION The mystery of the Indus Valley civilization fascinates many. Researchers tirelessly delve into the ancient era, studying old landmarks and artifacts to piece together the civilization’s history. A relic that propels this pursuit is the Pashupati Seal found in the ancient city of Mohenjo-Daro. The artifact’s varied interpretations provide insight into the civilization’s religious customs. This small relic holds powerful clues to the vast puzzle of the Indus Valley civilization. Measuring a mere 3.56 cm by 3.53 cm and 0.76 cm thick, the tiny seal is crafted from soapstone. The discovery was made in 1928-1929, with estimates placing the seal’s creation between 2350-2000 BCE. The seal’s central figure – a man with a horned headpiece – disrupts the norm of animals being the primary characters in Indus Valley seals. This man, perched on an elevated stage in a yoga pose, has three elongated, sharp-featured faces. His arms display a wealth of bangles stretching from wrist to shoulder, while necklaces cover his chest. Tassels on a belt adorn his waist. The intricate art of the Indus Valley civilization shows various plant-eating wild animals surrounding the seated man.Depictions of a rhino, an elephant, a buffalo, and a tiger, with the tiger appearing to attack the man, fill the seal. There are also two goats near the figure, their purpose – whether as animals or design elements of the platform – remaining unclear. Undeciphered Indus Valley civilization script adorns the seal. The seal’s purpose remains unknown but could have been a trading tool or an amulet, going by the hole seen on other seals. Thus, the seal might have been an identity marker for a community or worn as a status symbol. A number of historians have shared thoughts about a small seal’s scene. Most believe the human figure sitting is Shiva or Rudra, his other name. This idea came from John Marshall, an archaeologist and Director-General for the Archaeological Survey of India. He pointed out four reasons for his theory. First, the seated man’s three faces match some images of Shiva, who sometimes has four or five heads that look like three from the front. Second, the headpiece horns might depict Nandi, Shiva’s bull. Third, the man’s yoga pose links him to Shiva, who is seen as the first yogi and yoga’s source. Fourth, wild animals around the man might tie to Pashupati, another Shiva form known as ‘the animal king’, giving the seal its name. However, some have disagreed. Doris Srinivasan, Indian studies professor, argues the figure is a god that’s half man and half buffalo. She thinks the figure has cow ears, not three faces. Since their society relied on farming, cattle were essential, and a cattle god fits. Others have a slightly different idea. They believe the seal shows asura, a type of demon, rather than a god, but still half man and half buffalo. They say this could be a depiction of Mahishasura, a known asura who was defeated by Goddess Durga. Durga’s tiger, Dawon, might be the one attacking the figure in the seal. Some historians believe the figure might resemble gods from Vedic tales, such as Agni, Indra, and Varun. Leaving behind religious views, the seal also gives clues about yoga’s history in India. The figure’s pose, called Mulabandhasana, is a hard yoga posture. It demands flexible knees, hips, legs, ankles, and feet. Its presence on the seal of the Indus Valley civilization suggests advanced yoga was practised in the Indus Valley, indicating yoga may have started before or during their civilization.

Who is Vishnu and Garuda?

Who is Vishnu and Garuda? Vishnu stands as one god within the Hindu trio known as the Trimurti. This trio, consisting of Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva, each bear different responsibilities concerning our world. While Brahma’s job involves creating the universe, Shiva’s duty calls for its destruction. In contrast, Vishnu preserves and safeguards the universe. Vishnu’s role entails returning to earth during hardships, reestablishing the equilibrium of good and evil. Currently, Hindus believe Vishnu has reincarnated nine times. They also believe a final reincarnation will happen before this world’s end. People who worship Vishnu, known as Vaishnavas, view him as the supreme god. They see the remaining gods as minor or semi-gods. Vaishnavas hold Vishnu in exclusive admiration. This single-minded devotion to Vishnu is coined Vaishnavism. image of lord vishnu and garuda , pc-google images Garuda, a significant figure in Hindu myths, is a bird, which could be a dragon or eagle. Vishnu, a deity, considers this bird his mountain.The Rig Veda, an ancient text, compares the sun to a bird soaring in the sky. This eagle bring the celestial ambrosia plant from the sky to earth. In the epic tale of Mahabharata, it’s said that Garuda and Aruna, the sun god Surya’s charioteer, were brothers. Garuda’s mom, Vinata, considered as the birds’ mother, was fooled into being a servant to her sibling and fellow spouse, Kadru, the Nagas (snakes) mother. image of lord vishnu and garuda , pc-google images The continuing enmity between birds, especially Garuda, and snakes is believed to have resulted from this. The Nagas agreed to release Vinata if Garuda could obtain a draught of the elixir of immortality, either amrita or soma. Garuda accomplished this feat, endowing the snake with the ability to shed its old skin. On his way back from heaven, he met the god Vishnu and agreed to serve as his vehicle and as his emblem. Garuda. Krishna Garuda. Krishna ascending on Garuda, Satyabhama, opaque watercolor, gold and silver on paper, Bundi, Rajasthan, India, c.1730. At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. One document describes Garuda as emerald green, with a dragon’s beak, round eyes, golden wings and four arms, and a dragon-like chest, knees and legs. He is depicted as an anthropomorphic figure with wings and hawk-like features. His two hands are folded in prayer (anjali mudra) and the other two hold an umbrella and a pot of amrita. Sometimes Vishnu rides on his shoulders. Images of Garuda are used by Vishnu devotees to show their affiliation. Coins from the Gupta period feature such images. With the spread of Hinduism, Garuda traveled to Nepal and Southeast Asia, where he is often depicted on monuments. He is related to the royal families of several countries in Southeast Asia. image of lord vishnu and garuda , pc-google images

God Of Love – KamaDev

God Of Love – Kama Dev In the ancient Indian scripture Rigveda, we first meet Kamadeva (kamadev). His name joins ‘kama,’ meaning desire, and ‘deva,’ God, and thus he’s known as the ‘God of Desire’. An interesting way to picture him? Imagine a person flying on a parrot, holding a bow made from a sugarcane stalk. Now, think of the bow string – it’s a line of buzzing bees! As for his arrows, they’re not the usual ones. They’re flower-tipped, symbolizing desire. That’s Kamadeva’s unique way to spread love – those arrows can make anyone fall in love! Tale of Lord Shiva and kamadev Kamadeva was cursed by Shiva and was finally brought back to life only after Shiva and Parvati were happily married! There could be two reasons for this. For starters, Kamadeva was considered a part of the Vaishanava tradition, thought to be Vishnu and Lakshmi‘s son. Later on, Krishna took over as the ideal lover. Krishna, one of our most widely beloved gods, is perceived as the timeless lover alongside Radha and the gopis. In Mathura, there’s even a trace of a festival dedicated to the local god of love – Madana, that was absorbed by Krishna’s followers. There is celebration in the city that used to be the Madana Leela is now honored as Krishna’s Raas Leela! Kamadeva, a character dating back to the Rigveda, has a name that simply means ‘God of Desire.’ His description is vivid, involving him riding a parrot and holding a bow crafted from a stalk of sugar-cane. This bow is strung with a line of bees that hum. His arrows? They’re not your common ones. They’re flower-tipped, representing desire itself! Supposedly, their influence can make anyone fall in love! The Indian Kamadeva, the Greek God Eros, and the Roman Cupid share clear similarities in storytelling. The most outstanding story is when Kamadeva disturbed Lord Shiva‘s meditation to help Parvati, a king’s daughter, get his attention. Shiva, upset by the intrusion, lashed out at Kama with a curse. The love God returned to life once Shiva and Parvati tied the knot. It appears Kamadeva never truly bounced back as there aren’t many stories about him afterward.

Kissa Shiva Ka In Mahabharata

Kissa Shiva ka In the classic Hindu legend, the Mahabharata, there’s a tale told by Bhisma to Arjuna. It’s about a clash between Shiva and Daksha. Daksha snubs Shiva by not inviting him to share in a special ritual. In response, Shiva wrecks Daksha’s ceremony. This incident is said to have taken place in a location known as Ganga-dvara. Many people think this place is what we now call Haridwar. Our epic does not talk about Sati. The common tales say she’s Daksha’s kid and also Shiva’s spouse. They say she ended her life on her dad’s fire altar. Why? Because he did not invite her husband to his event. Not a single mention of Sati’s lifeless body held by Shiva. Or about pieces of it scattering across India. Those places later became known as Shakti-pitha, places with temples to a Goddess. The tales of Sati and Shiva only started to come out between 500 AD and 1000 AD. The Mahabharata is much older, dating back to 100 BC. The story of Mahabharata introduces Shiva’s spouse as Parvati. Shiva’s partner, however, is named Uma in the older Kena Upanishad, where Shiva represents the ultimate life force, Brahman. Here, no reference to Sati exists. This means that the concept of Shiva with two brides—one the offspring of Daksha, the other the child of Himavan—materialized later in time. Notably, despite Shiva’s austere lifestyle, his initial partner Sati was a Brahmin’s child, and his subsequent spouse Parvati was a Kshatriya’s daughter. People often link Shiva’s beginnings to the Veda, around 1000 BC. The god Rudra, a bit of an enigma, embodies this link. He’s a wild dweller, a cattle guardian, and has ties to both illness and healing. He wields a bow, uses an arrow to halt the first father’s pursuit of his daughter. Daksha’s link to Rudra appears later on. Then come tales of his marriage and offspring. All this shows how Shiva’s tales have evolved with time, geography, different cultural needs, and obstacles. The time after 1000 BC saw the flourish of Vedic culture, set amid Ganga and Yamuna’s doab. It was here that people built upon Vedic practices, holding tightly to their nomadic past with no temples or persistent shrines. Epic tales of Devas battling Asuras began here. It was said that Devas and Asuras, despite being half-brothers and children of Prajapati, the first being who later was known as Brahma, fought fiercely. The root of their conflict?- was Resources. In about 500 BC, our material-focused world met new ideas from monks originating further along the Ganga River. Regions like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Bihar birthed these thoughts. Buddhism stands out among these monk-led orders. Buddha, the originator, was once a recluse who morphed into a family man, according to Buddhist legends. The Mahabharata introduces us to Shiva, a recluse who also becomes a family man. The Ramayana adds to Shiva’s story, explaining how Shiva helped the Ganga river descend from heaven to bring revival to deceased kin. By the year 500 AD, tales of Shiva had hit the mainstream. He dared to challenge both Buddhism and the established Vedic practices. Shiva was portrayed as a hermit-turned-householder, representing a rejection of monastic life. He also disrupted Vedic yagna, a clear refusal of Brahmanical ceremonies. His depictions cropped up on India’s west and east coasts, promoted by Kalchuri, Chalukya, and Pallava rulers overseeing trade and ports. Temples presented him overpowering Ravana, the Ramayana’s antagonist, when he tried to seize Shiva’s Mountain home, Kailash. Around the year 1000 AD, Brahmins and kings reached further into tribal lands. Here, they tried to please the Goddess with Tantra rituals. These involved blood, alcohol, and sex. Images of Shiva prostrating before Kali were common. He would seek her assistance in wars, provide offspring for her, and partake in meals from her kitchen. Once the untamed Goddess got attention from Shiva, who was no longer an ascetic, she turned domesticated. By the year 1500, Islam firmly roots itself in India. The act of eating meat becomes associated with outsiders, leading to an intrigue of contamination. Popular trends now lean towards purification ceremonies. Shiva’s previous tie with tribal people and the ritually unclean cremation site is subtly reduced. An increasing number of deities known for consuming blood begin to prefer a vegetarian diet – a transformation first initiated by Jains, and later adopted by Brahmin wanderers such as Shankaracharya. Muslim leaders perceive the divine in a formless manner, hence the Shiva-linga symbol becomes more abstract, signifying the soul, while its phallic nature becomes less notable. The devotion to the blood-calling Goddess prevalent in Bengal, Assam, and Odisha presents an alternative to the more orthodox adoration movement focused on Ram and Krishna, where the sensual shifts into a spiritual, conceptual, and asexual sphere. In our modern era, ‘sanatana dharma’—or a timeless, steadfast faith—is becoming a popular tagline for Hinduism. This term, native to Vedic, Buddhist and Jain texts, essentially relates to theories of reincarnation, where the world and life have no origin or termination. Everything flows cyclically, diverging from the Christian and Islamic belief in a single life. ‘Sanatana dharma’ does not imply that Hinduism, Buddhism, or Jainism are unchanging faiths. There exist both consistencies and inconsistencies, changes springing from various historical and geographical circumstances, which birth the variety and dynamism of traditions. No need exists for their unification. By the year 1500, India is firmly under Islam’s influence. Consuming meat becomes associated with foreigners, implying contamination. Rituals for cleaning grow in popularity. Shiva’s prior association with tribal people and the symbolically unclean cremation site gets less attention. More blood-thirsty goddesses switch to plant-based diets, an idea first introduced by the Jains, but later adopted by wandering Brahmins like Shankaracharya. Under the new Muslim governance, the divine has no physical form. Shiva-linga begins to represent the soul abstractly, reducing its phallic connotation. In Bengal, Assam, and Odisha, the devotion to the goddess who thirsts for blood opposes the purist worship of Ram and Krishna. Here, all things sensual